I feel like a balloon going up into the atmosphere, looking, gathering information, and relaying it back. Rachel Rosenthal, 1985

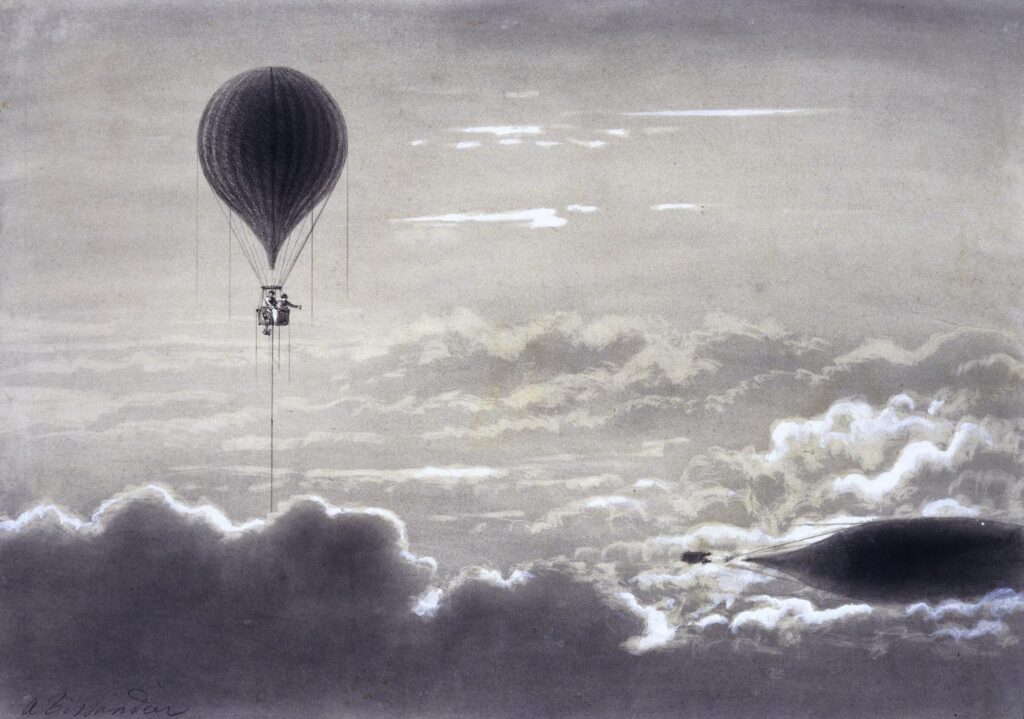

Last April 2019, Sounding Out! published my two-part article, “On the poetics of balloon music,” exploring sound, listening, and the atmosphere through the object of the balloon. The first part focuses on late 18th-century balloon travels and the descriptions of silence in the upper air that constituted a staple of Victorian balloon memoirs and literature of the time. Ascending above the noise of the industrialized city, the first balloonists were constructing a sonic identity rooted in the privilege of buoyancy and constructs of the sublime, harmony, and silence that excluded other ways of sounding.

The sight of boundless space and the quietude of the higher regions of the atmosphere inspired colonial narratives of territorial expansion. Sounds produced outside this imperialist worldview were perceived as invasion, contamination, and noise. By establishing an early connection between the exploration of the atmosphere and a listening ear based on elitism, race, and class, the article goes on to analyze some contemporary sound-art practices that use balloons to explore the atmosphere and that take on the challenge of creating a more inclusive relationship with the medium of air.

Against Levity: Experimental Music and the Latex Balloon

Part 2 of this article features an interview with composer and sound artist Judy Dunaway, who has been developing sculptural sonic performances with balloons for over 25 years. Dunaway’s work with the balloon as a sound producer has been the exclusive focus of several records (e.g., Balloon Music, Mother of Balloon Music), scores, sound sculptures, solo performances, ensembles, and installations. In this interview, Judy Dunaway talks about how her balloon compositions are in active dialogue with questions relating to feminism, body/mind, ecology, civil rights, memory, and the overall creation of musical expression and lexicon that lives outside a classical heritage.

As Dunaway points out, the balloon as a musical instrument bypasses dominant hierarchies of music production, leveling the access to experimentation and sonic textures that are restricted by expensive electronic technology. Besides democratizing sound, the latex balloon functions as a resonant chamber, offering an embodied and inclusive mode of listening through the vibration of its membranes. This object duality of sounding and sensing opens up room for what the scholar Steph Ceraso calls a multi-modal listening that plays with the body, affect, behavior, design, space, and aesthetics.

“From my earliest work with balloons as musical instruments, I instinctively knew that I must limit myself to the balloon and my body. This required that the balloon function not only as a musical appendage by which I may transmit sound, but also one that transmitted vibrations back to me through its sensitive body. (…)” Judy Dunaway, The Balloon Music Manifesto

Sounding Out! articles:

On the poetics of balloon music: Sounding Air, Body and Latex (Part 1)

On the poetics of balloon music: Sound Artist Judy Dunaway (Part 2)

*Brief review of these articles on the polish magazine Glissando: http://glissando.pl/aktualnosci/prasowka-29-04/

Carlo Patrão